There are thousands of species of corals and other invertebrates that can be found in reef environments, and the giant clams are certainly some of the most impressive and interesting. They can be quite eye-catching due to their sometimes mammoth sizes and beautiful appearances, but there’s a lot more to them than just good looks. So, I’ll introduce you to this clan of clams, collectively known the tridacnines, and explain why they’re so unique.

To start, there’s a good reason for calling them giants, as the largest of the twelve species in the family (Tridacna gigas) can grow to well over a meter in length and weigh well over 300 kilograms. Even the smallest tridacnine (T. crocea) can grow to 15 centimeters in length, which is still quite large for a clam, and the rest of the species fit somewhere in between these two. Most of them can grow to over 30 centimeters, though.

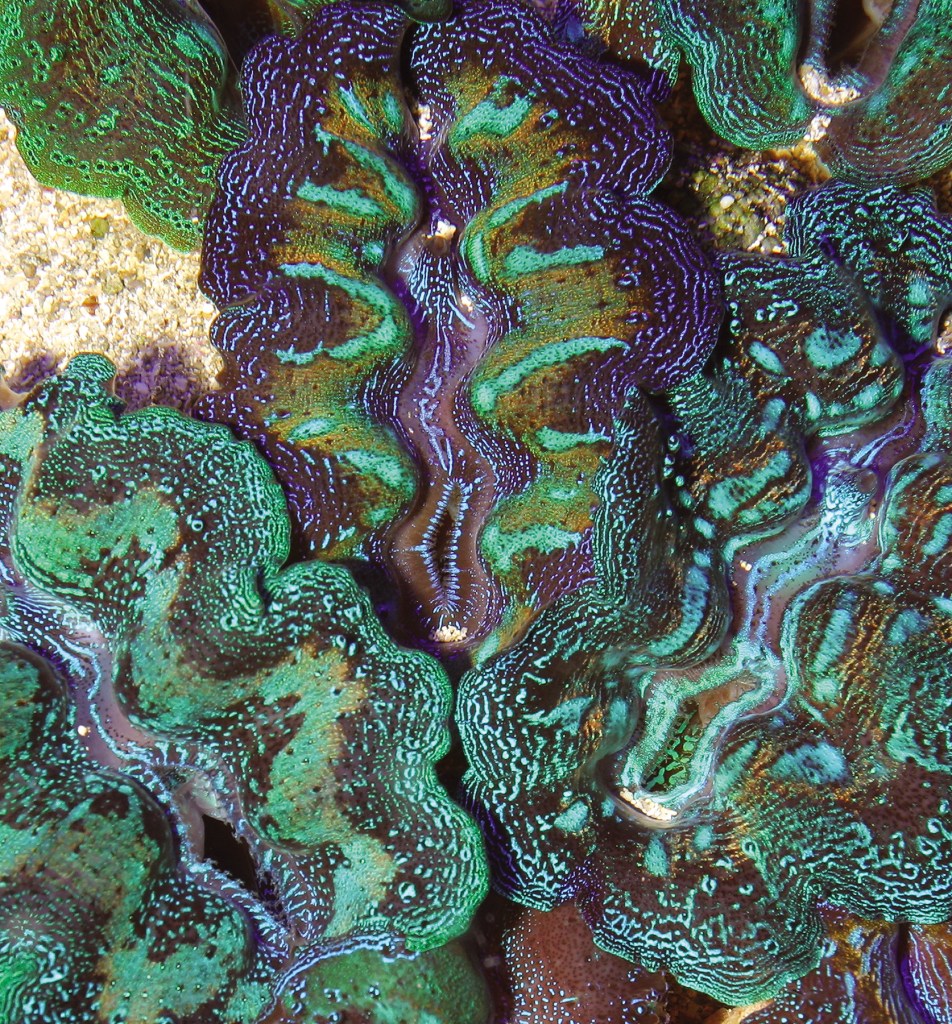

Aside from this, these clams are also biologically distinct from other sorts of clams for a number of other reasons, the most visually obvious of which is the nature of their mantle. This feature is the soft tissue part of all clams that envelops the body of the animal and forms its shell by precipitating hard calcium carbonate material around it. However, when it comes to giant clams, the mantle does much more than build their protective two-part homes. In their case, the mantle encloses all the internal organs and builds the shell, but it also typically extends well outside the top of the shell. It’s the usually colorful, patterned fleshy part that makes them so attractive, and it has a good reason for being unusually large and extendable.

While the vast majority of clams are filter-feeders that rely on sieving tiny plankton and other food particles from surrounding waters, the giant clams also carry a full compliment of single-celled photosynthetic algae in their mantles, which provide them with an additional, internal source of food. These algae, commonly known as zooxanthellae, are the same sorts of microscopic organisms that live inside reef-building corals, providing them with much of their nutritional needs, as well.

In corals and giant clams alike, the zooxanthellae produce food (primarily glucose) through the process of photosynthesis, and in both situations they can make more than they need for themselves. In fact, under optimal conditions, the zooxanthellae can actually make far, far more food than they need to keep themselves alive and well. Then, somehow, a host clam is able to coax this excess food from the zooxanthellae and use it itself. How much can a host clam get? Enough food to completely cover their caloric needs when well-lit. Thus, they literally live off light to a large degree, albeit in a roundabout way.

Now, if I tell you that the zooxanthellae are kept in high numbers within a host’s mantle tissue, it should be easy to see why the mantle is large, and typically extends well outside the shell. Yes, it’s a solar collector of sorts, as the mantle spreads out of the host’s shell in order to keep the greatest amount of zooxanthellae-occupied tissue illuminated as possible. And that means more food, of course. At this point I’d imagine that you can see why giant clams sit upright with their exposed mantle tissue facing the Sun instead of on their sides, and are only found in shallow well-lit waters, too.

Still, in addition to the nutrients supplied by a host’s complement of zooxanthellae, giant clams can also filter-feed like other clams. Basically they use their gills as strainers and collect particulate matter that’s found in the seawater they live in, and then they eat and digest the digestible part of whatever they ingest. This is how giant clams can acquire some of the nutrients they need, but it’s important to note that they can’t get everything they require via filter-feeding, and their relationship with zooxanthellae is obligate. In other words, unlike other sorts of clams, they cannot rely on filter-feeding alone and they must have a healthy complement of zooxanthellae and plenty of sunlight to survive.

And that’s not all. On top of utilizing their zooxanthellae and filtering food particles, giant clams can also absorb various things directly from seawater. In fact, some nutrients, like nitrogen and phosphorus, are primarily taken directly from the surrounding seawater, as they can be absorbed directly into a giant clam’s tissues by specialized cells that cover the surface of the mantle. Nitrogen can be taken up in the form of ammonia, ammonium, and/or nitrate, all of which are found in low concentrations in the environment, and phosphorus can come in the form of phosphates, which are present in low concentrations, too. Even small amounts of amino acids can be taken in, as are trace elements and other such things that naturally occur in seawater.

Things don’t end there, either. Zooxanthellae can also reproduce quickly inside a healthy host, and would actually create an overload if excess numbers of them were not regularly cleared out of the tubular system inside the mantle. So, many are ejected from the system, which is connected to the stomach, and passed though the digestive tract undigested. However, some excess zooxanthellae may be kept and used as yet another source of nutrition. Some of the zooxanthellae are “harvested” from the mantle by specialized cells that move around throughout the clams and their blood, and are then digested inside these cells rather than in the stomach. So, it’s easy to see that giant clams are some amazing animals for sure, having four means of covering their nutritional needs.

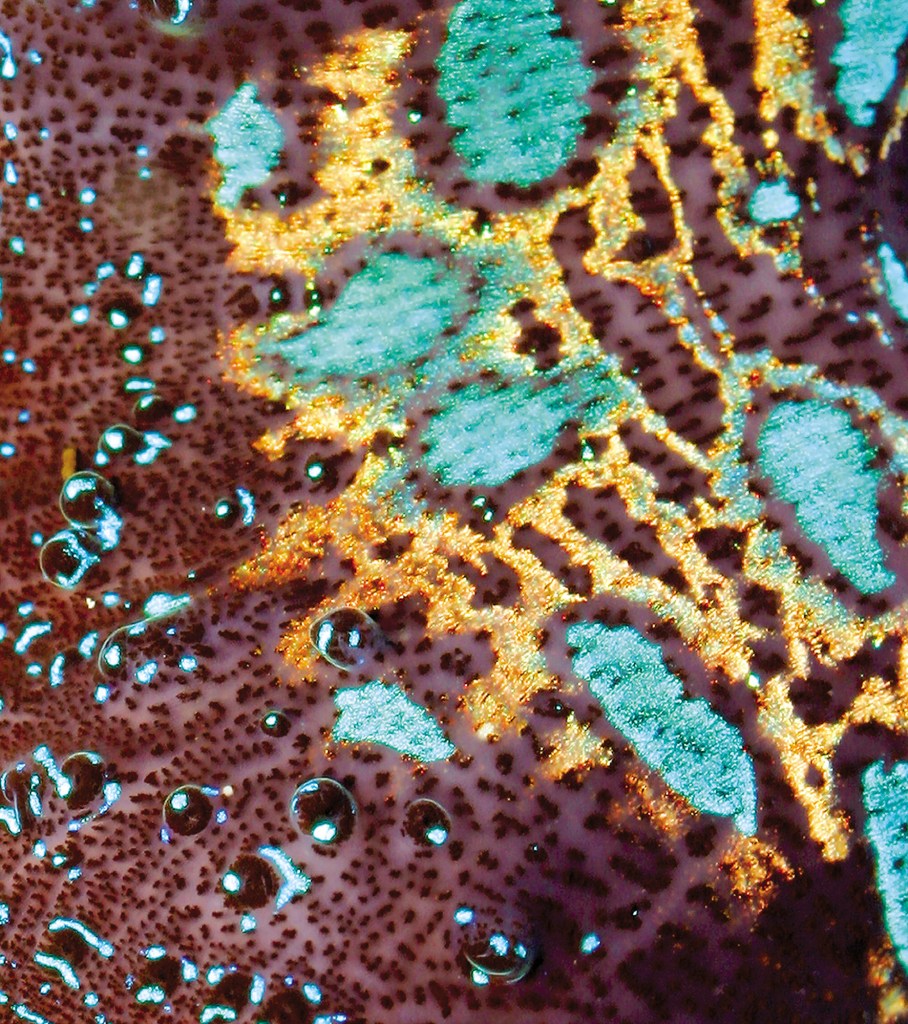

When it comes to why their mantles look the way they look, giant clams can produce numerous pigments, and their complements of zooxanthellae make their own pigments, too. So, the appearance of the mantles is actually a product of things made by the host and the hosted. The zooxanthellae make pigments used in the process of photosynthesis, like chlorophyll and peridinin, as well as a few others, and the pigments created by the clams are used primarily as sunscreens that protect both of them from excessive light. The mantle also contains some tiny structures called iridophores, which are made of small groups of specialized cells. These contain stacks of miniscule reflective platelets, and they also act as UV-protective sunscreens. It’s these little reflectors that are responsible for the iridescent sheen seen on some giant clams and some of the colors of the mantle, as well.

Still, nobody really knows why their mantles look the way they do when it comes to putting all these colors into mantle patterns. Giant clams can be covered by a seemingly endless array of not just colors, but patterns, and sometimes it seems like every individual of a given species seen on a dive looks at least a little different. Many may look similar overall, but some will look nothing like the others. Thus, at least to some to some degree, the colors and patterns seem to be rather random, as each species has a range of colors/pigments it seems to be able to make, and then uses them in different quantities and arrangements of spots, stripes, blotches, borders, etc.

It has been thought by some that the colors/patterns on the mantle have something of a camouflage effect, as they can break up the outline of the exposed fleshy mantle, but this isn’t the case. While diving I’ve found numerous relatively drably colored clams with mottled mantle patterns that were pretty well camouflaged. However, I could obviously still see them anyway. Likewise, if you move too close to any but the largest giant clams they can see you coming and will usually jerk the mantle into the shell as you approach, often giving away their own position. I’d miss many of them if they just sat still, but my eyes regularly pick up on the jerking motion of the mantle much more easily than on their actual mantle color or pattern. Thus, some tridacnines are rather well hidden at a distance and may not be seen by something quite far away, but others are either very obvious and/or give their positions away themselves. So, it’s unlikely that the colors/patterns have anything to do with camouflage. Besides, it would seem likely that one pattern would work better than the others and would eventually become dominant within a species, as the less-camouflaged clams would be more likely to be eaten by predators.

By the way, I wasn’t kidding about them seeing you, as the mantle can also have a number of dark-colored simple eyes on its surface. In fact, a single clam may have several thousand eyes. They aren’t very fancy, and they can’t produce a real picture like our eyes do, but they do allow giant clams to sense which way the Sun is, and to detect shadows, different visible colors, UV light, and movement, too. So, mantles often have dark spots on them in addition to everything else, and the distribution of the eyes can be quite random at times, as well. In some cases the eyes are found relatively widely spaced around the edge of the mantle, but in other cases they may be very tightly spaced, actually touching each other. Then again, they may also be scattered randomly all over the mantle in high numbers or low. Again though, there are no answers as to why there’s so much variability.

And that’s it for your introduction. As you can see, these clams are quite special, and can be appreciated for more than just their size and looks.

James W. Fatherree