One of the reasons I wrote my first book about giant clams (Giant Clams in the Sea and the Aquarium, 2006) was that I kept finding inaccurate information about them being circulated in the reef aquarium hobby. Amongst it all, there was a bunch of stuff about their husbandry requirements that was outright wrong and I had proof of that living in one of my own aquariums for several years. With the help of the internet, word had spread through the hobby that it was impossible to keep a tridacnine alive in an aquarium unless it was regularly fed with bottled plankton. Yet, I’d never fed my own clams anything. I asked quite a few advanced hobbyists what they thought about this and I got the same story again and again. They didn’t feed their clams, either. So, other hobbyists could get very different answers about this depending on where they looked and I wanted to help clear up this confusion.

Unfortunately, a secondary myth also evolved from the first one, which became known in the hobby as the “three inch rule.” The claim in this case was that immature tridacnines, those being under three inches in length (about 8cm), aren’t old enough to have built up a full complement of zooxanthellae in their mantle and will thus depend heavily on regular feedings in aquariums until they do so. In fact, some folks insisted that these smaller clams had to be fed several times a week to keep them alive. However, different tridacnines reach three inches at different points in their lives, all of them don’t become mature at three inches, and this idea that they needed to get to three inches in order to possess an adequate load of zooxanthellae was utter nonsense.

That might not sound like a big deal and it has occurred to me that non-aquarists and newbies might have no idea why this was such an issue in the first place. So, let me say a few things about planktonic foods and aquariums before continuing to the tridacnine nutrition stuff.

There’s absolutely nothing wrong with high-quality plankton-in-a-bottle products, which are literally bottles containing live (and sometimes preserved) plankton of various sorts. In fact, adding phytoplankton and/or zooplankton products to a reef aquarium can be highly beneficial to its inhabitants and I used a variety of this stuff (very sparingly) for many years. Various kinds of soft and stony corals will eat plankton, as do many filter-feeding organisms like porcelain crabs, fan worms, and tunicates.

Some plankton may also be beneficial to tridacnines, at times, and it certainly isn’t bad for them. However, adding too much plankton-in-a-bottle to a reef aquarium is a good way to ruin it, in the same way that dumping in too much fish food can. Or, at the least, it can lead to a whole lot of extra cleaning. The problem is that any uneaten food will decay in the aquarium and lead to elevated levels of dissolved nutrients in the water, which is a bad thing.

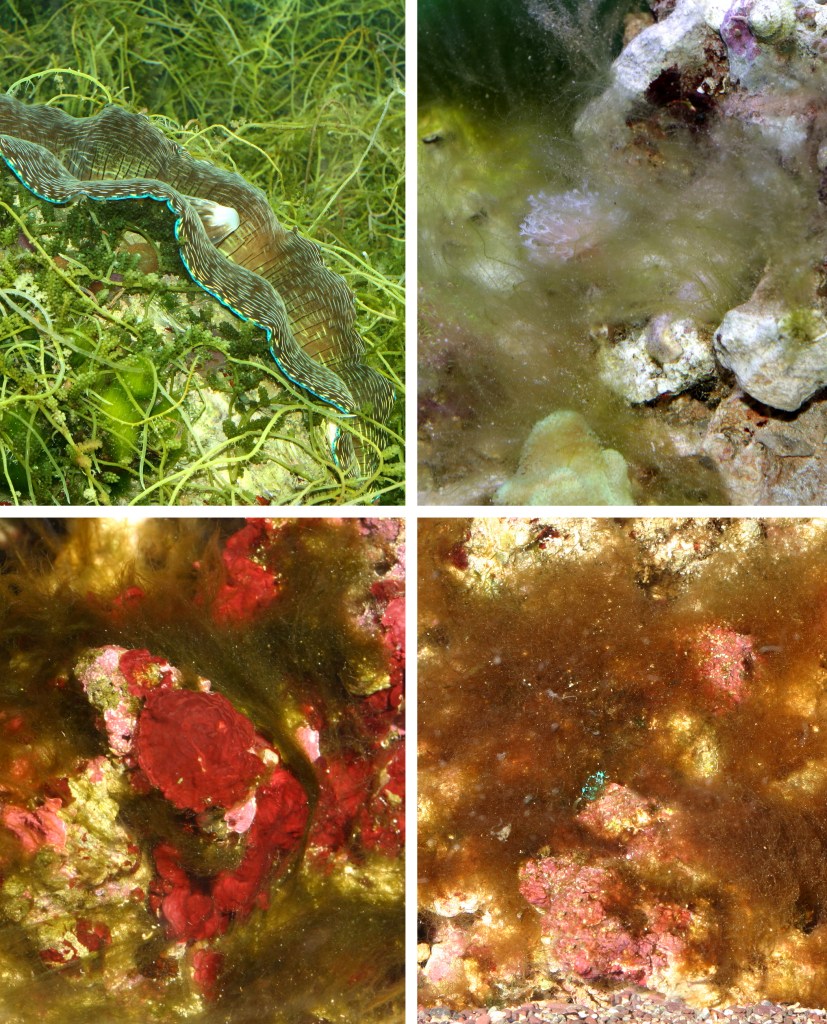

When plankton (or fish food) is added to an aquarium, some will be eaten, but some will not be. So, every time it’s added, there will be an excess that degrades water quality to some degree and that can lead to the rapid growth of unwanted/nuisance algae if it’s not dealt with through appropriate filtration and regular, periodic water changes. If nutrient levels aren’t kept sufficiently low, aquarists have to spend more time cleaning, and if algal growth really gets out of hand, it can even smother corals, clams, and other sessile invertebrates by overgrowing them.

Not good at all!

Elevated nutrient levels, phosphate in particular, can also chemically inhibit the formation of calcium carbonate by stony corals, clams, and coralline algae, etc. So, none of these can grow normally if nutrient levels are not kept in check.

If you don’t have any experience with reef aquariums, I’ll tell you that keeping nutrient levels low is one of the most difficult parts of long-term maintenance and that adding too much food can make it nearly impossible. Aside from that, plankton-in-a-bottle products tend to be rather costly and frequent use can add up.

So, the bottom line is that adding such products to an aquarium can be expensive and it can actually do more harm than good, especially if they’re being used (too) frequently. That’s why I felt the need to show people, exhaustively, that tridacnines do not require the use of plankton-in-a-bottle when kept in well-run reef aquariums. It may provide some benefit at times, if not overused, but once more I’ll say it – I’ve kept numerous tridacnines in aquariums long-term without feeding them anything and so have a lot of other hobbyists.

Let’s move along now and get to those details of tridacnine nutrition, taken from scientific studies rather than anecdotal aquarist experiences.

To start, there were studies done by Trench et al. (1981) and Klumpp et al. (1992), which were some of the first to take a good look at the specific roles of zooxanthellae in the tridacnines’ nutrition. After numerous experiments these researchers concluded that neither maxima nor gigas could live and grow normally using only what their zooxanthellae could give them. More specifically, Trench et al. wrote that maxima couldn’t even stay alive if it depended only on its zooxanthellae, while Klumpp et al. wrote that gigas could stay alive but couldn’t maintain normal growth rates. Thus, it seemed that both of these species required a considerable amount of particulate matter in their diets in order to live and grow normally.

If we only looked at what these initial studies reported, it would seem clear that tridacnines must filter-feed in order to live and grow. However, this conclusion was argued against then, further studied later, and is considered outdated now. I’ll go through the details to clear things up.

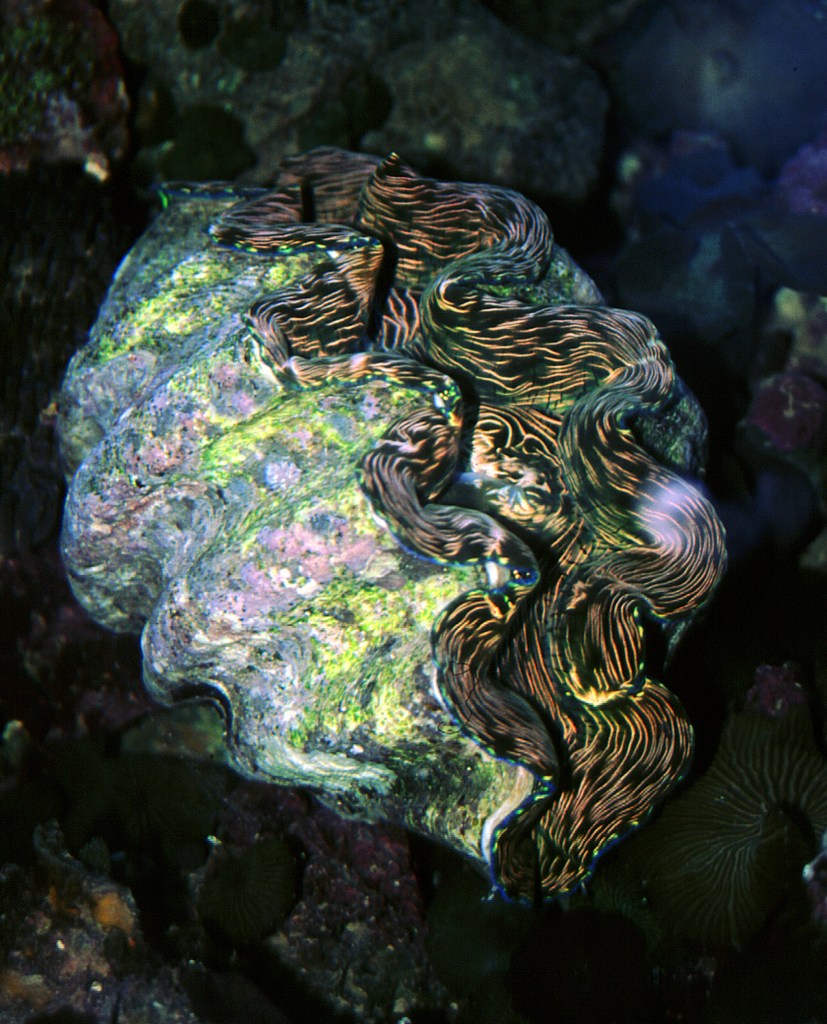

Zooxanthellae and Autotrophy:

To figure out how much a tridacnine can rely on its complement of zooxanthellae, basically you’d need to determine how much organic carbon and energy (C/E) a tridacnine needs in order to get through the day, then figure out how much C/E in the form of glucose and such that the zooxanthellae can produce and give to their host. The zooxanthellae can definitely make more food than they need for themselves. So, it’s just a matter of determining about how much these algal cells can translocate (give away) to a host clam compared to how much the clam needs to survive. If the zooxanthellae can translocate as much (or more) C/E in a day than the host needs, then the host can be considered autotrophic, which literally means self-feeding. In such a case, a clam wouldn’t need to get any C/E from filter-feeding or any other source. However, there’s more to nutrition than getting enough C/E to stay alive.

It’s important to think about the C/E needed for growth and for reproduction, too. Getting just enough C/E from the zooxanthellae to simply stay alive doesn’t mean a tridacnine will get enough to grow, or to develop gonads and produce gametes, either. Thus, we can look at how well the zooxanthellae provide for their hosts in two ways.

The first is called CZAR by researchers, which is an acronym for Contribution by Zooxanthellae to Average daily Respiratory needs. It pertains to just getting by from day to day and is a measure of how much of a clam’s basic needs are covered. So, having a CZAR value of 100% would mean that a clam could get exactly enough C/E to survive, but no more than that. And, a value less than 100% would mean that a clam needs to get some C/E from a different source, while more than 100% would mean that it receives more C/E than it needs to live.

Then, there’s growth (and/or reproduction) on top of that, so I’ll use the acronym CZARG. This would be the percentage of a clam’s daily respiratory and growth/reproductive needs covered by the zooxanthellae, and having a CZARG value of 100% would make a clam truly autotropic with respect to C/E. It would be able to live, grow at a normal rate, and produce gametes without needing to filter-feed.

| Nutritional Priorities: Tridacnines obviously need nutrients in order to live, grow, and reproduce. However, these three things are not given equal priority when it comes to where/how nutrients are used when they are acquired, as respiratory needs always come first. When a clam gains nutrients in any form, it must cover what it takes to make it through the day first. It obviously wouldn’t make much sense to add on some shell growth if you’re going to die the next day, or to put a lot of energy into making gametes if you’re going to die before you can release them. So, respiratory needs (which may also be called basal or maintenance needs) are the most critical thing to think about when discussing nutritional budgets. Growth and reproduction, on the other hand, have variable priorities that change with respect to each other over time. Tridacnines, like basically everything else, are especially vulnerable to predators when they are small in size. Therefore, when a clam is young, it needs to put all that it can spare into growth so that it can get bigger (and safer) as quickly as possible. However, once a clam reaches a particular size and approaches sexual maturity, some nutrients will be diverted away from growth and into the production of gonads, and then into making sperm and eggs. Growth will slow down accordingly, of course, and if the clam was getting sufficient nutrients to grow normally, that should be enough for them to produce plenty of gametes. |

What Klumpp et al. found in 1992 was that the CZAR for gigas was over 100%, but CZARG was less than 100%. In other words, the zooxanthellae could provide enough C/E to keep the host alive under optimal conditions, but couldn’t provide enough to cover its requirements for normal growth. So, they wrote that gigas had to filter-feed if it was going to do much more than survive.

By doing a few experiments they determined that a small gigas, about 4.2cm in length, could potentially satisfy as much as 65% of its total C/E needs via filter-feeding. They also determined that this amount dropped steadily as the clams grew, until it fell to about 34% by the time the clams were 17cm in length. Thus, they supposedly depended less and less on filter-feeding and more and more on their zooxanthellae as they aged.

However, there are quite a few important details to take in to consideration here. For starters, gigas is just one species of tridacnine and what gigas needs may not be what another species needs. Additionally, the way that CZAR and CZARG values were calculated was soon found to be way off.

A full-size gigas can be more than twice as long and ten times heavier than the next largest species (derasa), and gigas can grow about ten times faster than the slowest growing species (crocea), too. Gigas also has gills that are quite unique and is the only tridacnine species with two sets of particle-collecting grooves on each one. Thus, gigas may be better at collecting larger amounts of particulate food (Norton & Jones 1992).

Regardless, when looking at tridacnines’ need to filter-feed (or not to) from another angle, Mangum and Johansen (1982) and Klumpp et al. (1992) also studied the amount of water some tridacnines pumped through their mantle cavity and over their gills, relative to their size. What was discovered is that gigas pumps though relatively huge volumes of water compared to other species. For example, a gigas may pump an incredible 14 times more water through its mantle cavity per hour than a squamosa of about the same size. So, these researchers came to the conclusion that gigas must be pumping so much more in order to get more food from the water, as more water moving through equals more particulate matter exposed to the filtering gills. Conversely, it would seem that squamosa needed only to move enough water through to get and to get rid of oxygen and carbon dioxide and thus wasn’t particularly reliant on filter-feeding.

Likewise, Klumpp and Griffiths (1994) found that a small gigas could pump water at greater than ten times the rate of crocea, squamosa, and hippopus at the same size. And, Klumpp and Lucas (1994) reported that derasa and tevoroa had relatively low pumping rates, moving water into the mantle cavity at about 1/7 the rate of a similar sized gigas (FYI: mbalavuana was called tevoroa at that time and I’ll use the correct name from here). They also reported that filter-feeding could provide at most 8% and 14% of respiratory (but not growth) demands of large and small derasas and mbalavuanas, respectively. However, that would only be the case if these clams could completely digest and use 100% of the C/E in the particulate matter they ingest, which is highly unlikely seeing that the other species studied can only use about 50% to 60% of the C/E contained in the particulates that they ingest. Only part of any food is fully digested and used, with the undigestable matter leaving as feces. Thus, those 8% and 14% numbers should probably be closer to 5% and 8%, and again, that’s only of respiratory needs.

Obviously, these other clams weren’t getting much C/E via filter-feeding in their natural environment. So, you can see that the feeding needs and habits of gigas are not equivalent to the needs/habits of these other species. The different species don’t just differ in size.

On top of all that, Klumpp et al. (1992) used a study area that had a higher concentration of carbon-containing particulate matter in the water than many other areas where tridacnines can thrive. The specific numbers don’t matter here, but the concentrations in other areas where tridacnines are found are often only half as much (or even less) as what Klumpp et al. used to come up with that 65% figure for gigas. So, you can see that the potential contribution of filter-feeding to nutrition can vary substantially not just from species to species, or from small size to large size individuals, but from place to place, as well. Oh yeah, and from time to time, too, as weather, wind, waves, etc. can significantly affect how much particulate matter is suspended in the water and available to a feeding clam. When waves get going, they stir up lots of stuff from the bottom, and when there are no waves the water tends to clear as many particles settle out and become unavailable.

| How much particulate matter and where? When talking about nutrition in the form of particulate matter, researchers usually don’t talk about the actual numbers of planktonic creatures floating and swimming around. Instead, they measure how much carbon is present in a given volume of water, which is incorporated into the various sorts of particles it contains. You can think of it as taking all the phytoplankton, zooplankton, and detritus (and anything else) found in a liter of seawater and measuring the total amount of carbon found in all of it. When studying gigas at Davies Reef lagoon, Australia, Klumpp et al. (1992) used a concentration of 97 micrograms of carbon per liter (µgC/l), which was the average amount of carbon not just in phytoplankton, or zooplankton, or detritus, but the total from all three along with bacteria and such. However, the range through the year actually changed from 78 to 116µgC/l and wasn’t some constant number that a gigas living there had access to 24/7/365. Also, if any part of that 97µgC/l was in the form inedible particles, like specks that were too small for gigas to collect with its gills and eat, then you’d also have to take that into consideration when figuring out the true degree that gigas can depend on particulate foods. In other words, if you put a gigas in a soup of carbon-rich detritus and plankton, but all the particles are too small (or too big) to eat, they aren’t going to help. This can be quite significant since some studies, like Blanchot et al. (1989), have showed that the vast majority of carbon (81% in some localities) is found in particles that are smaller than 3µm. That means much of it is indeed contained in particles that are too small to eat since tridacnines may not consume particulates smaller than about 2µm. Likewise, Klumpp and Griffiths (1994) decided to go with a local average value of 200µgC/l at Orpheus Island, Australia, in their study. Yet, Klumpp and Lucas (1994) used an average of only 65µgC/l, which was appropriate for the areas where many derasas and mbalavuanas live. And… Just to give you a few more numbers to pore over, in Blanchot et al. (1989), I found an average concentration of 62µgC/l for the central Great Barrier Reef, of 64µgC/l for an open reef at Guam, of 53 to 68µgC/l for Eniwetok lagoon, and for 31µgC/l for Eniwetok reef. Thus, it seems clear that in many environments where tridacnines can live, the amount of carbon present in particulates is actually substantially lower than the numbers used in the above-mentioned nutrition studies. |

Subsequently, the more recent studies by Klumpp and Griffiths (1994) and Klumpp and Lucas (1994) also took another look at the roles of zooxanthellae and filter-feeding and they both painted a very different picture. This was primarily due to a change in the way CZAR values were calculated, which produced results about three times greater than those reported in earlier studies.

Klumpp et al. (1992) had used a value of 30% for the maximum contribution of carbon by zooxanthellae when they calculated CZAR. In other words, they thought that the zooxanthellae could make X amount food and give 30% of X to their host while keeping 70% for themselves. However, it was determined by other studies that the percent of contribution by zooxanthellae was probably more like 95 to 97% with the zooxanthellae keeping a measly 3 to 5% of their food product for themselves and translocating everything else to their hosts (ex. Muscatine 1990, Fitt 1993, and Ambariyanto 2006). That changed everything, of course.

Let me make up an example here. If a hypothetical clam needs 6mg of carbon per day and its zooxanthellae can produce 10mg per day and translocate 30% of that to the clam, then the clam would get 3mg per day from the zooxanthellae. That’s only half of what it needs, though, and you might assume it needs to get another 3mg per day via filter-feeding just to stay alive. However, if the translocation value is increased from 30% to 95%, then the zooxanthellae’s contribution jumps from 3mg per day to 9.5mg per day – more than 150% of what the clam needs to stay alive. CZAR goes from 50% to greater than 150% and that means there’s an excess, which can be used for growth and reproduction. It also means that the clam in question doesn’t need to get any C/E via filter-feeding to stay alive. With this kind of excess, the CZARG values will also increase significantly.

This is exactly what happened, and we have to clear out those old CZAR/CZARG values and take a look at the results of the more recent studies. The 1994 paper by Klumpp and Griffiths (using a translocation value of 95%) reported that under optimal conditions, zooxanthellae could provide as much as 343% of the C/E needed by a large gigas to stay alive, 337% for a large crocea, 352% for a large squamosa, and 343% for a large hippopus. Likewise, the Klumpp and Lucas paper (1994) about mbalavuana and derasa (again, using 95%) reported that CZAR for large specimens was as high as 187%. And, Ambariyanto (2006) reported that it was as high as 261% for maxima.

With this in mind, you can go back to that first study I mentioned (Trench et al. 1981), which reported that maxima couldn’t even stay alive if relying only on its zooxanthellae. Change the 40% translocation rate they used to 95% and the CZAR more than doubles, increasing from 85% to 202%. So, in all cases, under optimal conditions, the zooxanthellae can provide far, far more C/E than these clams need to stay alive.

That’s some high CZAR values for sure, but what about CZARG? Klumpp and Griffiths (1994) also have data showing a CZARG of 233% for a large gigas, 274% for a large squamosa, 273% for a large crocea, and 238% for a large hippopus. Klumpp and Lucas (1994) reported CZARG of 146% for a large mbalavuana and derasa, too. Again, these values are for both respiration and growth.

All right, I’m on a roll and still need to go a little further. You may have noticed that the numbers I gave above were all for large clams, but what about smaller clams? As I mentioned at the beginning, there have been claims by some in the aquarium hobby that large clams are very different than small clams, as small clams rely much more heavily on filter-feeding to meet their needs. Again, the basic part of this claim was that small clams needed time (years) to grow their mantle and to build up a sufficient population of zooxanthellae to become autotrophic – and had to eat lots of plankton until that happened.

However, these assertions lead back to the earlier papers that I just went over above, when the translocation by zooxanthellae was thought to be only 30 to 40% and that filter-feeding could make up the difference. It’s also very important to note that Klumpp et al. (1992) only showed that a small gigas can potentially get as much as 65% of its C/E via filter-feeding, but certainly did not show that a small gigas had to get 65% of its C/E requirements via filter-feeding, as many people seemed to believe. That’s two different things.

So, let’s look at some CZAR and CZARG values for some small clams to clear up any possible confusion. The smallest clams offered for sale to hobbyists are usually around 4cm in length, but far more small clams are in the 5 to 10cm range. Keep this in mind when you see these CZAR and CZARG numbers coming up.

Mingoa (1988) found that 1.75cm gigas (smaller than what you can buy) had average CZAR values of only 92% under bright sunlight. Close, but not quite enough C/E from the zooxanthellae for basic maintenance. However, that was in 1988 and Mingoa, using unpublished data from Griffiths, had chosen a translocation value of 32%. So, you can see the same thing happening here for these little clams, too. Change the translocation value to 95% and CZAR values almost triple, to 273%.

In addition, Fischer et al. (1985), using a translocation value of 95%, reported a CZAR value for gigas of 149% for a 1cm specimen, 259% for a 1.15cm specimen, and 318% for a 1.55cm specimen. Again, these are all smaller than the smallest clams an aquarist can buy. Then, Klumpp and Lucas (1994) found CZAR to be as high as 178% for 2.2cm derasas and 2cm mbalavuanas, with CZARG values of 140% for both, while data from Klumpp and Griffiths (1994) shows a CZAR of 265% and CZARG of 191% for 4.2cm gigas, 233% and 206% for 2.4cm crocea, 186% and 118% for 4.2cm squamosa, and 300% and 30% for 4cm hippopus.

Yes, for some reason, in the Klumpp and Lucas (1994) study, hippopus had a CZAR of 300% but had a CZARG of only 30%, which makes it an outlier. However, the low CZARG for small individuals is apparently due to their exceptionally generous use of carbon in the shell (it’s made of calcium, carbon, and oxygen). For example, the authors reported that the shell of a 4.2cm gigas weighed about 5.5g, while the shell of a 4cm hippopus weighed in at a (relatively) whopping 12g. Hippopus starts making a much thicker/heavier shell than gigas (and the others) when still at a small size and it needs lots of carbon to do it.

However, by the time hippopus reached 7.7cm in length, it needed 4.6mg of carbon per day for maintenance and growth and got 3.5mg from its zooxanthellae (CZARG = 76%). And, by 15cm it needed 30.2mg/d and got 46.4mg/d (CZARG = 154%). Thus, hippopus can potentially start getting everything it needs from its zooxanthellae to grow normally somewhere between 7.7 and 15cm in length, probably moving into the green around the 10cm mark. Keep in mind that it can still get far more than what it needs to stay alive (like 3x more) even when it’s tiny, though.

Regardless, we can also go back even further to a couple more older studies and the smallest of all small clams. Fitt and Trench (1981), in their study of how squamosa acquired its zooxanthellae in the first place, reported that over a dozen specimens were raised from sperm and egg and maintained for 10 months in filtered seawater with no access to particulate foods at all. Now that’s a bunch of really small clams! I’ll also add that while Fitt and Trench didn’t do any experiments to determine CZARG, they did specifically point out that these clams didn’t just survive in the filtered water, but grew in size. The growth was a little slower than normal, but the light that they used in their experiments was also much, much dimmer than sunlight. Additionally, Fitt et al. (1986) wrote that during the first few days to several weeks of a clam’s life, the population of zooxanthellae grows exponentially as it fills the mantle and that the CZAR value accordingly increases from 0% to 100%. That’s within just the first few weeks of life when a juvenile tridacnine is barely big enough to be seen.

With all that covered, let me throw in a direct quote from Klumpp and Griffiths (1994): “All species and sizes of clam in this study (except for small Hippopus hippopus) obtain sufficient carbon solely from phototrophic sources to satisfy not only their routine respiratory needs (i.e. the CZAR value), but also the additional demand for carbon deposited into tissues and shell.” Here’s one from Klumpp and Lucas (1994), too: “Tridacna derasa is able to function as a complete autotroph in its natural habitat (down to 20m), and T. tevoroa (mbalavuana) achieves this in the shallower parts of its distribution (10 to 20m).” So, I think I’ve now shown that all of these tridacnines, at every size tested, were potentially fully autotrophic with respect to C/E (with the exception of small specimens of hippopus) and the data from these studies clearly show that tridacnines of any size shouldn’t need an additional source of carbon when living under ideal environmental conditions.

I’m still not done with this, though, and will now thoroughly beat a dead horse! Once again, there were those claims that small clams have relatively small mantles and so few zooxanthellae in their relatively small mantles that there’s just no way any of them can get much food from the zooxanthellae. However, the 1996 paper Relationships between size, mantle area and zooxanthellae numbers in five species of giant clam (Tridacnidae), by Griffiths and Klumpp, shows that while relative mantle surface area may increase with increased clam size, the zooxanthellae may or may not increase in density in the mantle with increased size, and the ratio of total numbers of zooxanthellal cells to the host’s total body mass actually goes down with increased host size. Thus, we have some confusing information again, and need to look at three different aspects of this study as they relate to crocea, derasa, squamosa, gigas, and hippopus (the 5 species in the study).

Griffiths and Klumpp found that there are actually several trends in the changes of mantle surface area compared to clam shell length. For example, at small sizes crocea may have the greatest mantle surface area compared to its shell length (MA:SL) while gigas can have the lowest, with the other species falling somewhere in between. However, as they all grow, some change places and gigas ends up in first place with the greatest MA:SL, while derasa ends up last. Regardless, for all species the overall MA:SL ratio goes up. The clams get bigger/longer and their mantles get larger a little faster. So, this tends to make the myth sound correct and this study was frequently cited as a source. There’s a lot more to this, though.

Next, the authors pointed out that when looking at how the population of zooxanthellae changed in relation to the shell length of the clams, they found things to be quite different for crocea, derasa, and hippopus. The population of zooxanthellae doesn’t go up proportionally to the increase in size (and thus the increase in mantle area) for these species. This means that for crocea, derasa, and hippopus the density of zooxanthellae in the mantle actually goes down with increased clam size. The opposite is true for squamosa and gigas, as the density of zooxanthellae in the mantle increases as the clams grow. This tends to make the claims above a little iffy.

It’s important to note that, so far, these have only been comparisons of mantle area and zooxanthellal population to overall size (shell length), but now we get to the increase in body mass. The mantle can get a lot longer and wider as a clam grows larger, but the mantle doesn’t get proportionally thicker. To the contrary, the body mass that’s underneath the mantle grows in length, width, and thickness (girth). Thus, the body’s increase in mass is much greater than that of the mantle.

Okay, so what does that mean? It means that even if the mantle increases in area with increased clam size, and the density of zooxanthellae in the mantle increases with increased clam size, the actual number of zooxanthellae per gram of clam body mass can still go down with increased clam size – and it does.

The authors found that regardless of the other trends, the ratio of total zooxanthellal population to a clam’s body mass still goes down for all five species as they grow larger. I quote, “Calculations of zooxanthellae numbers per gram flesh mass show that such densities decline with increasing clam size in all species sampled.” The only exception is when clams are very, very small (still less than a millimeter in length) and are still in the process of acquiring their initial populations of zooxanthellae.

On top of that, one thing that the authors did not find, discuss, mention, or even allude to is that smaller clams depend more on filter-feeding than larger ones. Actually, the purpose of the study was to see if there was a relationship between the things the authors looked at and the maximum adult size of the different species. They were wondering why gigas gets so big and crocea stays so small, etc. In addition, as if I haven’t said enough, Fisher et al. (1985) reported exactly the same thing in the results of their study of gigas 11 years earlier, writing that the number of zooxanthellae per gram of clam tissue actually decreases with increasing clam size.

Water depth/illumination, the amount of chlorophyll per zooxanthellal cell, how deep the zooxanthellae are in the mantle tissue, etc. also play roles in how much food the zooxanthellae can make (and translocate). And, now that you’ve read all this, I have to say the point is really moot anyway. I showed above that CZAR and CZARG, even for the smallest of clams, can be well over 100% regardless of mantle areas and zooxanthellal populations and densities. Still, at least you’ve now seen where those erroneous claims came from and why they can be confusing.

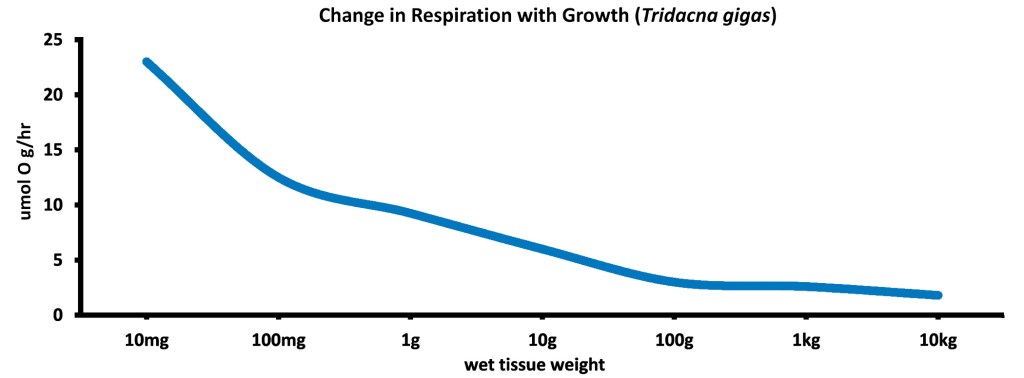

There’s one last piece of information to deal with here, though. Really, it’s the last one! You may not have picked up on it, but if you look at the numbers and the graph above, you’ll see that CZAR/CZARG values typically go up as clams get bigger – at the same time that the number of zooxanthellae per gram of clam tissue goes down. That’s confusing for sure since it would seem that CZAR/CZARG should go down when the density of zooxanthellae goes down.

The answer isn’t spelled out in the text of any of these papers, but it can be found in the data and was also noted by Fischer et al. (1985). What happens is that respiration rates generally decrease rapidly as tridacnines get larger. In other words, the amount of C/E needed to run each gram of clam tissue gets lower and lower as a clam gets older and older (with the apparent exception of hippopus for some unexplained reason).

For example, data from Klumpp and Griffiths (1994) shows that a 1g gigas (dry tissue weight) requires about 0.01 grams of carbon and an appropriate amount of oxygen per day for respiration, while a 10g gigas requires about 0.05g of carbon per day. Thus, when the clam’s tissue weight increased 10 times, the carbon requirement only increased 5 times, showing that the overall respiration rate went down. It went down a lot, really. So, there are fewer zooxanthellae per gram of clam tissue in bigger clams, but each gram of clam tissue needs less carbon, and the carbon needs drop faster than the relative density of the zooxanthellae does. Thus, CZAR/CZARG can go up over time instead of down and the riddle is solved.

Eating Particulate Foods:

With all that said, do tridacnines eat anyway, even if they don’t have to? Yes, they do (occasionally at least) and filter-feeding can potentially increase growth rates and/or survival rates, particularly when clams are small. They may not have to feed to get C/E when times are good, but it certainly looks like gigas does whenever it can, and there’s no doubt that all of the rest of them will take at least a little food (or maybe a lot) at times.

However, the quantity and quality can vary tremendously, and whether tridacnines feed or not may also depend on how much light they get and how big they are, etc. The bottom line is that tridacnines are considered to be rather opportunistic, meaning that if there’s food present, they’ll probably take some, and if there isn’t, they won’t. Lighting can change drastically through the hours, days, weeks, and years, as water clarity, the weather, and the seasons constantly change. The availability of various sorts of particulate matter can change significantly over short and long time spans, as well.

Still, even when tridacnines do filter-feed, things can get really weird, as there are numerous reports of clams eating particulate matter but then defecating all of it, and more. For example, Ricard and Salvat (1977) found that maximas would eat a common type of phytoplankton, the single-celled diatom Isochrysis sp., in one of their experiments. Then, the clams would poop out great quantities of it, undigested, along with a bunch of extra zooxanthellae. So, the clams were actively filter-feeding, but apparently weren’t using what they ingested. Very odd, indeed. By the way, the clams also dumped out just as much zooxanthellae when kept in filtered water with no food as they did when given food. Thus, filter-feeding didn’t seem to make any difference when it came to how much zooxanthellae was discarded.

Regardless, I’ve got more interesting information about exactly what they eat when they do. Like countless other biology students, I was taught that, for the most part, clams are picky eaters and that their gills filter out specific particles within a certain size range and density, which are further sorted before being ingested. Supposedly, the gills collect only the “right stuff” and the rest is either passed up entirely or is sorted out, collected, rolled into little pseudofeces, and dumped out.

Phytoplankton has been considered the right stuff, but zooplankton generally has not. To the contrary, zooplankters are typically a lot bigger than phytoplankton and are supposedly unwanted by clams. Thus, clams have often been thought to be strictly herbivorous, eating only phytoplankton, but not zooplankton.

However, this is incorrect, and numerous studies have shown that many clams do eat both phytoplankton and zooplankton, and other things (ex. Langdon & Newell 1990, Kreeger & Newell 1996, Tamburri & Zimmer-Faust 1996, Lehane & Davenport 2002, Wong et al. 2003). At least one study (Wong & Levinton 2004) even found that the clams they experimented with grew faster when given a mixed diet of relatively huge zooplankton and tiny phytoplankton than when given a diet of just one or the other. They also found that the survival rate for their clams was the same when fed only zooplankton, only phytoplankton, or both. They used Mytilus sp., which isn’t a tridacnine, but this was an eye-opening finding, nonetheless. Additionally, as I began to dig through all the references that deal with tridacnine nutrition, I found that quite a few researchers had written about tridacnines eating not just phytoplankton, but a whole lot of other stuff, too.

For example, going back to 1936, Yonge reported that some derasas’ feces included a few diatoms (a common type of phytoplankton), some fine filamentous threads of algae, and zooxanthellae (note that zooxanthellae are a type of dinoflagellate and dinoflagellates are also a common type of phytoplankton). He found that croceas ate small zooplankton (less than 14µm), as well. Mansour (1946a & b) also wrote that tridacnines ate zooplankton, as did Ricard and Salvat (1977). In fact, they collected some relatively large live zooplankton (using a 240µm sieve) and fed it to maximas under lab conditions, then reported that some fragments of the zooplankton were observed in the clams’ feces in less than 24 hours. The gills are thought to typically filter out fine particulates in the range of about 2µm to 50µm, but it seems that tridacnines can also ingest food items that are much, much larger than this. The same ability has been observed in studies of other bivalves, as well (ex. Tamburri & Zimmer-Faust 1996).

Anyway, in the same study, Ricard and Salvat also found that the feces of maximas living in the sea rather than the lab contained a variety of things, including plankton fragments, grains of sand, and some spicules (tiny parts of sponges). Likewise, Trench et al. (1981) found that maxima’s feces contained zooxanthellae, unrecognizable debris, and fragments of zooplankton.

A few years after that, Reid et al. (1984) wrote that gigas’ stomach in one study locality contained unidentifiable fragments of planktonic crustacea (zooplankton), diatoms, algal cells that looked like zooxanthellae, and sand, while those in another locality lacked the algal cells and contained more sand. Then, Klumpp et al. (1992), in their paper about gigas, reported that the particulates in their study area were “dominated” by detritus rather than phytoplankton, which the clams used to satisfy a significant proportion of their carbon needs. They also noted that gigas’ feces contained a little zooxanthellae and the rest was digested phytoplankton and detritus. Then, Maruyama and Heslinga (1997) reported that derasas’ feces in their study were comprised of shapeless debris and possibly degraded material, some diatoms, some zooxanthellae, some filamentous cyanobacteria, and some ciliates (animal-like single celled organisms).

Obviously tridacnines can and will eat a much broader range of particulates than what might be expected. Certainly, they could avoid ingesting relatively large zooplankton, which could easily be sorted out and discarded, if they couldn’t make use of it. Likewise, detritus can be especially rich in nutrients and must be usable, as well. It has been found in a digested state in the feces and it seems that some tridacnines can take advantage of the ubiquitous presence of this nutritious hodgepodge of particles.

Absorbing Nutrients:

Okay, under good conditions tridacnines can typically get enough C/E from their zooxanthellae to cover their needs and can also filter-feed to get more when necessary. Thus, it’s finally time to get to nitrogen and phosphorus, which are the other big nutrients that I bring up in my books.

First, I have to make it clear that filter-feeding can certainly provide more than just C/E. Phytoplankton, zooplankton, detritus, etc. all contain carbon, and nitrogen, and phosphorus, etc. and if they’re eaten, digested, and used, a clam can extract and use these substances for themselves. However, nitrogen and phosphorus are primarily taken directly from the surrounding seawater in forms other than plankton or detrital particles. In fact, these nutrients can be absorbed directly into a tridacnine’s tissues and can also be taken in with seawater and exceptionally fine particulates by specialized cells that cover the mantle.

Fankboner (1971) reported that the outer surface of the tridacnine mantle is covered by these microscopic structures, called pinocytosing (intaking) microvillous (tiny finger-like) epidermal cells, and that they can take in “phenomenal” quantities of both fluid and miniscule particulate substances. Goreau et al. (1973) wrote about the uptake of various substances directly from seawater, as well, and there’s a stack of more recent papers that discuss the uptake of dissolved substances.

Nitrogen can be taken up in the form of ammonia/ammonium (NH3/NH4) and/or nitrate (NO3), all of which are found in low concentrations in the environment, and phosphorus can come in the form of phosphate (PO4), which is present in low concentrations, too. Even small amounts of dissolved amino acids can be taken in, as well as trace elements and other such things that naturally occur in seawater, albeit in low concentrations (ex. Goreau et al. 1973, Wilkerson & Trench 1986, Belda & Yellowlees 1995, Hawkins & Klumpp 1995, Ambariyanto & Hoegh-Guldberg 1999).

| Ammonia and Ammonium I said that tridacnines can take up ammonia and ammonium (NH3/NH4), but I need to say a little more here. When ammonia is present in seawater most of it is converted instantaneously to ammonium, as it can pick up an extra hydrogen ion from the water. Ammonium can drop the extra hydrogen and instantaneously go back to being ammonia, too. Yes, chemistry can be weird. So, the net effect of this is that these really aren’t distinct chemicals as far as we’re concerned. Tridacnines can take up both and they always have detectable levels of both in their blood (Fitt et al. 1993). |

Exactly how much “stuff” is taken in this way as opposed to filter-feeding hasn’t been quantified (as best as I can tell), but I did find it amazing that Hawkins and Klumpp (1995) reported that when gigas was kept in particle-free filtered seawater in their study, the rate of nitrogen uptake directly from the water in the form of ammonia increased by 100%. In other words, when one source of nitrogen was cut off (the filter-feeding) the clams just switched over to another source – and in a big way. The studied clams actually doubled their daily intake of nitrogen via absorption!

In addition, they can also shift from one form of nitrogen-based stuff to another if necessary, as Fitt et al. (1993) showed. They found that when ammonia was present in relatively high concentrations, the uptake of nitrate was strongly repressed. But, when the concentration of ammonia dropped, the clams simply switched over to taking whatever nitrate was available.

While there has been some debate about exactly what happens between the host and the hosted once the clams have these nutrients in their possession, the general idea is that the zooxanthellae can use them to build things a clam can use, like amino acids, and then donate these to the host along with glucose. The clams then use and incorporate some of these zooxanthellae-produced substances into their tissues. However, clam tissue also gives off some nitrogen as a metabolic waste product (so do you), which would have to be expelled if not for the zooxanthellae. Instead of getting rid of it, this waste nitrogen, which happens to be in the form of ammonia, goes right back to the zooxanthellae, which recycles it along with “new” nitrogen from the environment to form even more useful substances.

This process is apparently exceptionally efficient, as Hawkins and Klumpp (1995) reported that the zooxanthellae help to recycle and conserve almost 100% of all nitrogen given off by the host’s tissues and that about 95% of the nitrogen released in the form of amino acids by the zooxanthellae were used by host tissues afterwards. In other words, once some nitrogen is taken from the environment, it’s held on to and recycled very tightly. How phosphorus moves between the two partners hasn’t been examined in as much detail as nitrogen, though, and still is not well understood at this time (Ip et al. 2021).

Anyway, the bottom line here is that the tridacnines can acquire the nitrogen and phosphorus they need in various forms from the surrounding water by means other than filter-feeding. We looked at some experiments above that showed that clams could survive and grow in filtered water, but the filtered water they lived in still contained nitrogenous and phosphoric substances, which the clams could extract and use. That’s how they were able to make it without doing any filter-feeding.

Aquaculture facilities that raise tridacnines have taken advantage of this ability for a long time now, as many of them use some method or another to add dissolved nitrogen to the systems that their clams are raised in. Chemicals like ammonium nitrate, ammonium chloride, ammonium sulfate, and sodium nitrate can be added to system water, where they dissolve and make nitrogen available to the clams. Other clam farmers may just urinate in their systems, providing nitrogen in the form of urea (R. Perrin, owner, Tropicorium, pers. comm. 2005). Then, given sufficient lighting and good water quality, the clams can show greatly accelerated growth with rates sometimes increasing by as much as 75% (ex. Hastie et al. 1992, Fitt et al. 1993, Heslinga et al. 1990, Ellis 2000).

Digesting Zooxanthellae:

Plants and other photosynthesizing organisms are all well known for their seemingly magical ability to take various sorts of simple inorganic substances from their surrounding environment and combine them to make complex and useful compounds, some of which are used to build new cells and other structures, and to reproduce. Zooxanthellal cells are obviously doing the same thing when living inside tridacnines (and outside of them, too). Thus, they can potentially provide a host with nutrients in one last way, as they can actually become food themselves.

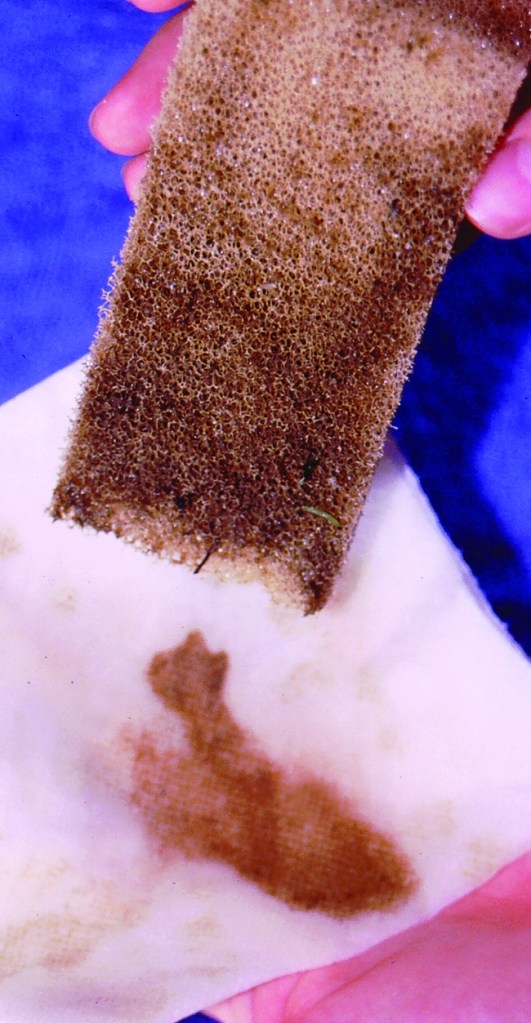

Zooxanthellae reproduce quickly inside a healthy tridacnine and could potentially create a population overload if excesses are not cleared out of the Zoxanthellal Tubular System they’re held in. So, many cells are ejected from the system of tubes, move into the stomach, and then travel out the back end of the clam’s digestive system and through the exhalent siphon. However, it seems that a small number of them may be “harvested” from the ZTS by specialized amoeba-like cells that move around throughout a clam’s tissues and in its blood. When this happens, the zooxanthellal cells are then digested inside these amoeboid cells, rather than in the stomach (Fankboner 1971).

Maruyama and Heslinga (1997) also reported that some of the zooxanthellae were definitely being consumed in some way, after they found that zooxanthellal cells were reproducing in the mantle at a higher rate than they were being dumped out of the rear. Thus, it seems that some of them are used like any other ingested phytoplankton to supply carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, and other required substances to the host, although the digestive process is entirely different.

Yes, tridacnines are a nutritional miracle…

References:

Ambariyanto. 2006. Estimating contribution of zooxanthellae to animal respiration (CZAR) and to animal growth (CZAG) of giant clam Tridacna maxima. Journal of Coastal Development 9(3):155-162.

Ambariyanto and O. Hoegh-Guldberg. 1999. Net Uptake of dissolved free amino acids by the giant clam Tridacna maxima: alternative sources of energy and nitrogen. Coral Reefs 18:91-96.

Belda, C.A. and D. Yellowlees. 1995. Phosphate acquisition in the giant clam-zooxanthellae symbiosis. Marine Biology 124:261-266.

Blanchot, J., L. Charpy, and R. LeBorgne. 1989. Size composition of particulate organic matter in the lagoon of Tikehau atoll (Tuamotu archipelago). Marine Biology 102:329-339.

Borneman, E.H. 2003. The food of the reefs, part 6: particulate organic matter. Reefkeeping 2(2): reefkeeping.com/issues/2003-03/eb/index.htm

Ellis, S. 2000. Nursery and Growout Techniques for Giant Clams (Bivalvia: Tridacnidae). Center for Tropical and Subtropical Aquaculture Publication 143. 99pp.

Fankboner, P.V. 1971. Intracellular digestion of symbiotic zooxanthellae by host amoebocytes in giant clams (Bivalvia: Tridacnidae), with a note on the nutritional role of the hypertrophied siphonal epidermis. Biological Bulletin 141:222-234.

Fatherree, J.W. 2006. Giant Clams in the Sea and the Aquarium. Liquid Medium Publications, Tampa. 228pp.

Fischer, C.R., W.K. Fitt, and R.K. Trench. 1985. Photosynthesis and respiration in Tridacna gigas as a function of irradiance and size. Biological Bulletin 169:230-245.

Fitt, W.K. 1993. Nutrition of giant clams. In: Fitt, W.K. (ed.) Biology and Mariculture of Giant Clams. ACIAR Proceedings No. 47, Canberra. 154pp.

Fitt, W.K. and R.K. Trench. 1981. Spawning, development, and acquisition of zooxanthellae by Tridacna squamosa (Mollusca, Bivalvia). Biological Bulletin 161:213-235.

Fitt, W.K., C.R. Fisher, and R.K. Trench. 1986. Contribution of the symbiotic dinoflagellate Symbiodinium microadriaticum to the nutrition, growth and survival of larval and juvenile tridacnid clams. Aquaculture 55:5-22.

Goreau, T.F., N.I. Goreau, and C.M. Yonge. 1973. On the utilization of photosynthetic products from zooxanthellae and dissolved amino acids in Tridacna maxima cf. elongata (Mollusca: Bivalvia). Journal of Zoology (London) 169:417-454.

Griffiths, C.L. and D.W. Klumpp. 1996. Relationships between size, mantle area and zooxanthellae numbers in five species of giant clam (Tridacnidae). Marine Ecology Progress Series 137:139-147.

Hastie, L., T.C. Watson, T. Isamu, G.A. Heslinga. 1992. Effect of nutrient enrichment on Tridacna derasa seed: dissolved inorganic nitrogen increases growth rate. Aquaculture 106:41-49.

Hawkins, A.J.S. and D.W. Klumpp. 1995. Nutrition of the giant clam Tridacna gigas (L.). II. Relative contributions of filter-feeding and the ammonium-nitrogen acquired and recycled by symbiotic alga towards total nitrogen requirements for tissue growth and metabolism. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 190:263-290.

Heslinga, G.A., T.C. Watson, and T. Isamu. 1990. Giant Clam Farming. Pacific Fisheries Development Foundation (NMFS/NOAA), Honolulu. 179pp.

Ip, Y.K., M.V. Boo, J.S.T. Poo, W.P. Wong, and S.F. Chew. 2021. Sodium-Dependent phosphate transporter protein 1 is involved in the active uptake of inorganic phosphate in nephrocytes of the kidney and the translocation of Pi into the tubular epithelial cells in the outer mantle of the giant clam, Tridacna squamosa. Frontiers in Marine Science 8: 655714.

Klumpp, D.W. and C.L. Griffiths. 1994. Contributions of phototrophic and heterotrophic nutrition to the metabolic and growth requirements of four species of giant clam (Tridacnidae). Marine Ecology Progress Series 115:103-115.

Klumpp, D.W. and J.S. Lucas. 1994. Nutritional ecology of the giant clams Tridacna tevoroa and T. derasa from Tonga: influence of light on filter-feeding and photosynthesis. Marine Ecology Progress Series 107:147-156.

Klumpp, D.W., B.L. Bayne, and A.J.S. Hawkins. 1992. Nutrition of the giant clam Tridacna gigas (L.). I. Contribution of filter feeding and photosynthates to respiration and growth. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 155:105-122.

Kreeger, D.A. and R.I.E. Newell. 1996. Ingestion and assimilation of carbon from cellulolytic bacteria and heterotrophic flagellates by the mussels Geukensia demissa and Mytilus edulis (Bivalvia, Mollusca). Aquatic Microbial Ecology 11:205-214.

Langdon C.J. and R.I.E. Newell. 1990. Utilization of detritus and bacteria as food sources by 2 bivalve suspension-feeders, the oyster Crassostrea virginica and the mussel Geukensia demissa. Marine Ecology Progress Series 58:299-310.

Lehane, C. and J. Davenport. 2002. Ingestion of mesoplankton by three species of bivalve; Mytilus edulis, Cerastoderma edule, and Aequipecten opercularis. Journal of the Marine Biological Association U.K. 82:615-619.

Mangum, C.P. and K. Johanson. 1982. The influence of symbiotic dinoflagellates on respiratory processes in the giant clam Tridacna squamosa. Pacific Science 36:395-402.

Mansour, K. 1946a. Communication between the dorsal edge of the mantle and the stomach in Tridacna. Nature (London) 157:844.

Mansour, K. 1946b. Source and fate of the zooxanthellae of the visceral mass of Tridacna elongata. Nature (London) 158:130.

Maruyama, T. and G. Heslinga. 1997. Fecal discharge of zooxanthellae in the giant clam Tridacna derasa with reference to their in situ growth rate. Marine Biology 127:473-477.

Mingoa, S.M. 1988. Photoadaptation in juvenile Tridacna gigas. In: Copeland, J.W. and J.S. Lucas (eds.) Giant Clams in Asia and the Pacific. ACIAR Monograph Number 9, Canberra. 274pp.

Muscatine, L. 1990. The role of symbiotic algae in carbon and energy flux in reef corals. In: Dubinsky, Z. (ed.) Coral Reefs: Ecosystems of the World, Vol. 25. Elsevier, Amsterdam. 550pp.

Norton J.H. and G. Jones. 1992. The Giant Clam: An Anatomical and Histological Atlas. ACIAR Monograph Series No. 14, Canberra. 142pp.

Reid R.G.B., P.V. Fankboner, and D.G. Brand. 1984. Studies on the physiology of the giant clam Tridacna gigas Linne – I. Feeding and digestion. Comparative Biochemical Physiology 78A(1):95-101.

Ricard, M. and B. Salvat. 1977. Faeces of Tridacna maxima (Mollusca-Bivalvia), composition and coral reef importance. In: Proceedings of the Third International Coral Reef Symposium. Miami. 495-501.

Rossbach, S., R.C. Subedi, T.K. Ng, B.S. Ooi, and C.M. Duarte. 2020. Iridocytes mediate photonic cooperation between giant clams (Tridacninae) and their photosynthetic symbionts. Frontiers in Marine Science 7(465):1-13.

Tamburri, M.N. and R.K. Zimmer-Faust. 1996. Suspension feeding: Basic mechanisms controlling recognition and ingestion of larvae. Limnology and Oceanography 41(6):1188-1197.

Trench, R. K., D. S. Wethey, and J. W. Porter. 1981. Observations on the symbiosis with zooxanthellae among the Tridacnidae (Mollusca, Bivalvia). Biological Bulletin. 161:180-198.

Wilkerson, F.P. and R.K. Trench. 1986. Uptake of dissolved inorganic nitrogen by the symbiotic clam Tridacna gigas and the coral Acropra sp. Marine Biology 93:237-246.

Wong, W.H. and J.S. Levinton. 2004. Culture of the blue mussel Mytilus edulis (Linnaeus, 1758) fed both phytoplankton and zooplankton: a microcosm experiment. Aquaculture Research 35:965-969.

Wong, W.H., J.S. Levington, B.S. Twining, N.S. Fisher, K.P. Brendan, and A.K. Alt. 2003. Carbon assimilation from rotifer Branchionus plicatilis by mussels, Mytilus edulis and Perna viridis: a potential food web link between zooplankton and benthic suspension feeders in the marine system. Marine Ecology Progress Series 253:175-182.

Yonge, C.M. 1936. Mode of life, feeding, digestion and symbiosis with zooxanthellae in the Tridacnidae. Scientific Reports of the Great Barrier Reef Expedition 1:283-321.

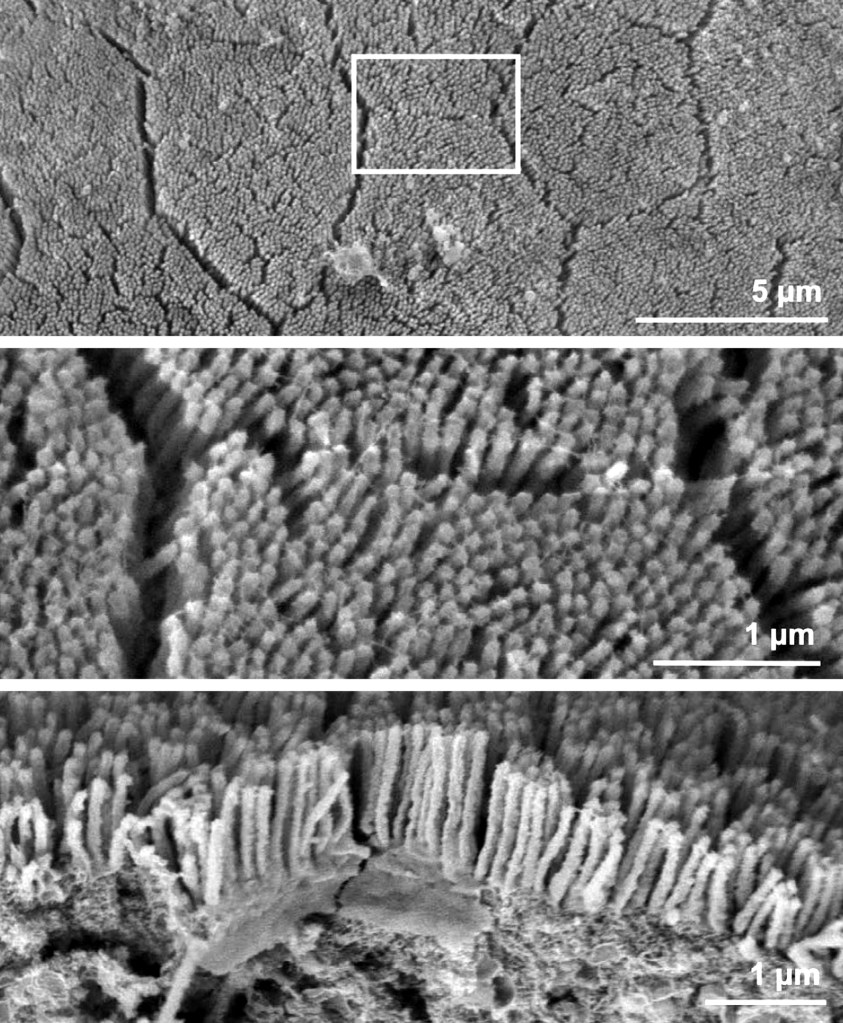

*Microscope images of the upper mantle. Images licensed under Attribution 4.0 International (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/) in Rossbach, S., R.C. Subedi, T.K. Ng, B.S. Ooi, and C.M. Duarte. 2020. Iridocytes mediate photonic cooperation between giant clams (Tridacninae) and their photosynthetic symbionts. Frontiers in Marine Science 7(465):1-13.